A Better Way to Hire: the Case Study

Candidates need to be sure they like the job; companies need to know that a candidate can do the job.

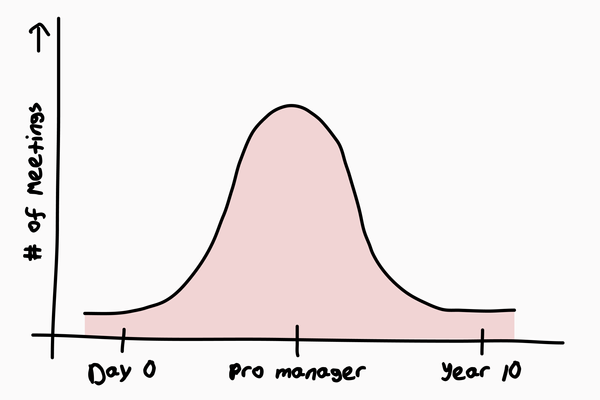

When companies raise a lot of money, the first thing they do is hire a lot more people. The theory goes that more people do more, so capital—and thus hiring—will drive more growth.

But in practice, this theory is not true. The problem is that individual performance follows a log scale: an A player does 10x as much as a B player; B player 10x as much as a C player; etc. And A players are rare.

It took me hundreds of hires as CEO of Albert, the banking app I founded in 2016, to fundamentally understand this. Only the most exciting, prestigious companies in the world can hire many A players quickly. For everyone else—especially startups finding their footing—hiring A players is rare, and hiring a lot of B players does not translate to productivity growth.

Hire stars

When you work with a star, you know it immediately. If you're not sure, they are not a star.

You'll search for a star—the A player— for a while, think you've found them, but have many false starts. When you do find stars, it will transform your organization. Companies are on a mission to hire as many stars as possible.

Years ago at Albert, we hired a junior frontend engineer who seemed promising. One Friday afternoon he decided that our internal customer support and financial advice application (now used by more than 500 agents and advisors, handling 50,000 messages/day) should have dark mode. Before he left that night, the application had dark mode, with no input from the design or product teams. Dark mode is still heavily used today. A couple years later, the same engineer converted hundreds of thousands of lines of code from python 2 to python 3 in two days. This was an epic feat. Both of these projects would have taken a large organization weeks and dozens of people to complete. Fast invention and iteration is the lifeblood of a growing company, which only stars can drive.

A better way to hire

Interviews are a terrible gauge of likelihood to succeed at a company, while the take-home case study is a great predictor of success.

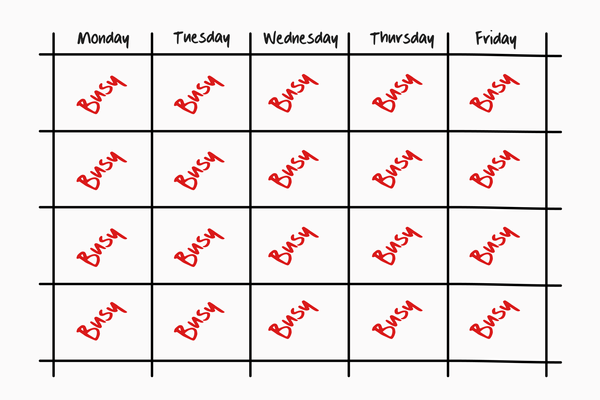

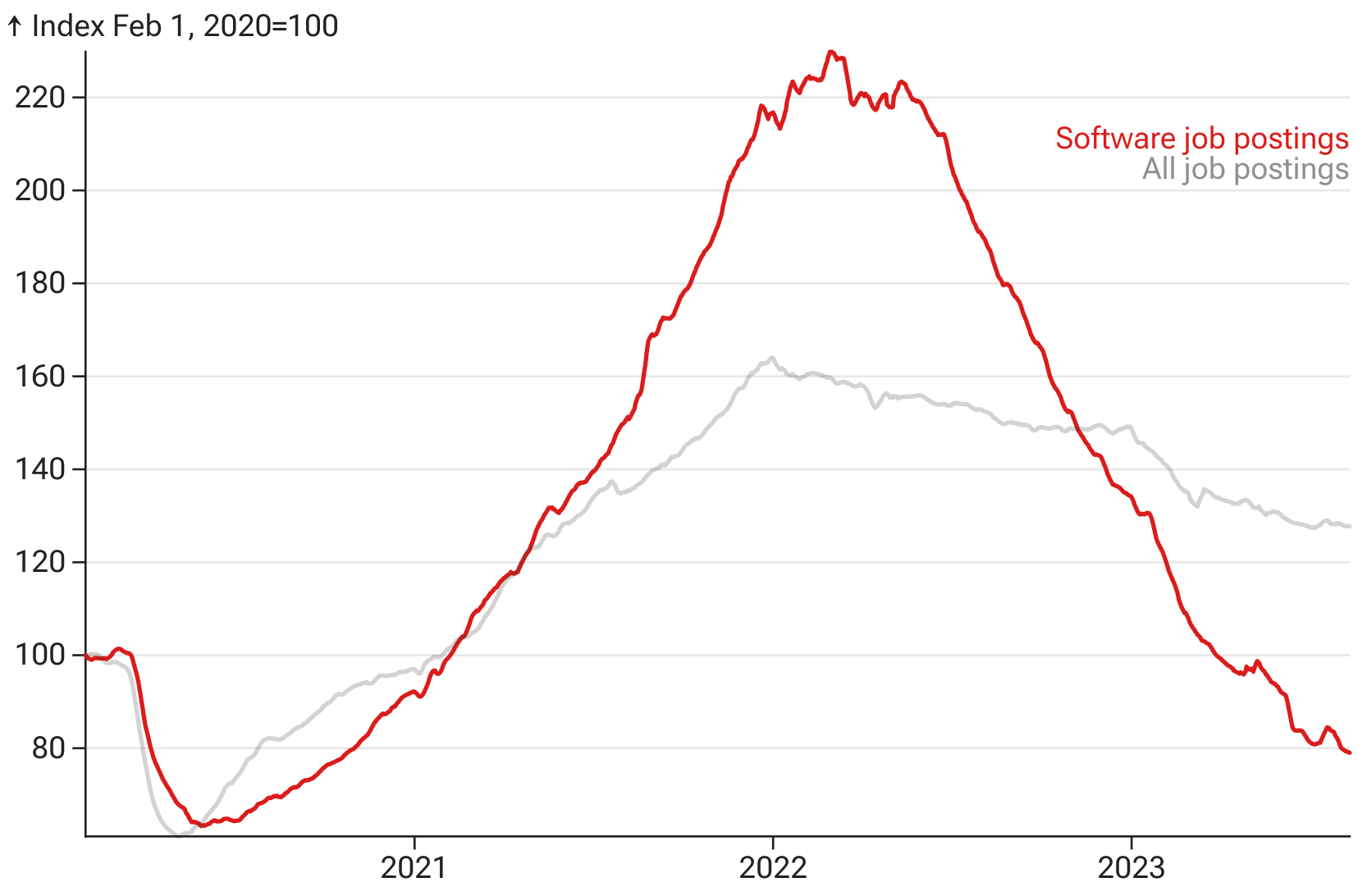

The goal of a great interview process is to find stars. When the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to zero at the start of the pandemic, the startup hiring market became grossly imbalanced. Money was cheap, companies raised a lot of it and used it to hire quickly. There was an explosion of job openings in multiple sectors. Candidates started getting multiple lucrative job offers within days of starting their job search. It became impossible to get to know a candidate before making an offer.

Software job posts on Indeed

Before 2020, every candidate that interviewed at Albert completed a job specific, take-home case study that took up to four hours to complete. In 2020, candidates began refusing the case study because the interview process at other companies was faster and simpler. We stopped the case study. Not only were we spending less time with candidates, we found that interviews alone are a terrible predictor of a candidate's likelihood to succeed at a company.

In 2023, with the job market normalizing, we have been able to restart the case study. We resurrected our best hiring tool.

The case study

Candidates need to be sure they like the job; companies need to know that a candidate can do the job.

How does a company know if a candidate is good at a job if they don't see the candidate perform the job? How does the candidate decide if they like the job if they don't try the job? Sitting through six hours of interviews with prospective coworkers answers neither side's question.

The solution: a take-home case study for every candidate. Below are examples for three roles.